There’s No Denyin’ Brian Survivin’

Finally performing under his own name, Brian Wilson brings the house down.

It was with great trepidation that I earmarked June 21st to see the Boston concert debut of fellow-former-EQ-coverboy Brian Wilson in that classical bastion, Symphony Hall in downtown Boston. Now, more than a few of you might denigrate the value of the Beach Boys legacy in popular music, but you’d have to answer to me. I was never suckered into the Pendleton shirt wardrobe, the general appearance of the mayonnaise-headed performers themselves, or some of the lyrics, but I was extremely moved by the musicality of it all.

The composer (Mr. Wilson) cleverly interspersed jazz chord changes over doo-wop structures and thick, never-heard-before voicings in the background vocals. I sat up and took notice. Slowly, the instrumentation caught up to the rest of these divergences, and soon cellos, bass harmonicas, harps, and flutes adorned these tales of teen angst. Then the lyrical content began its admittedly slow ascent to the top, and the package became complete.

This was no ordinary surf group — believe me. I knew my slavish devotion had finally paid off when the almost-classically constructed instrumental introduction remained unedited on the hit “California Girls,” and I was completely vindicated with the release of Brian’s masterpiece, Pet Sounds, in 1966. As a matter of fact, I was invited into Brian’s home two weeks before the release of said album for an advance solo listening party.

It was the era of the piano-in-the-sandbox and the soda fountain-in-the-living room. This New Yorker was bowled over by the music, and felt like he was in the company of a latter-day Mozart or Beethoven (the Beethoven comparison is closer, as Wilson is stone deaf in one ear). Pet Sounds scared the Beatles into creating Sgt. Pepper, but their creation was a pale second to their original muse. Today, 33 years after Pet Sounds’ release, I still can’t figure out the opening chord changes to “Don’t Talk, Put Your Head On My Shoulder.”

But Brian had his share of setbacks. Like any great genius, he was belittled and misunderstood, and, with aggravated drug use, it all came crashing down around him. Misplaced in the custody of some Dr. Nick-like shaman, he slipped further and further away from the creation of his former glories. His long-suffering wife left with the kids, and it seemed to the faithful fan like he/she would never hear the likes of that musical Camelot again. And that is why, as I walked into Symphony Hall last month, I silently prayed that everything would be OK. That Brian would surmount the recent deaths of his brother Carl and his mother Audree, leaving him the sole- (soul) surviving Wilson.

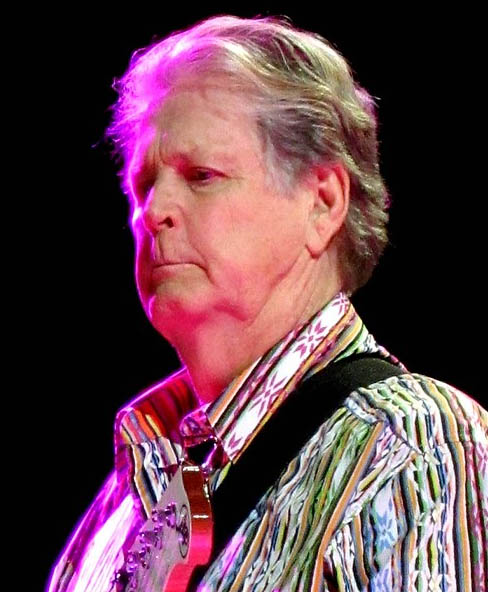

As the house lights dimmed, a makeshift screen on the side of the stage unspooled a 20-minute cinema-verite video account of what I just wrote in the preceding paragraphs. The image transformation of the bright-eyed strapping youth on Dick Clark’s ’60s TV dance party, American Bandstand, into the foreboding Broderick Crawford look-alike of today was instantly sobering. But Brian was now situated in a new, sane marriage replete with two infant children and a new-millennium grin that seemed to never quit. The lure of audience-interaction was finally too much for the Master. The screen was taken away and the audience rose for its first of many standing ovations, as the man himself strode to center stage.

To open, he chose the 1964 oldie, “She’s Not The Little Girl That I Once Knew.” In retrospect, gender aside, it seemed like the perfect introduction lyrically, in a vaguely analogous way. His vocal range has been decimated by the years, and he chooses to shy away from his trademark falsetto, leaving it for the other nine singers on stage to sort out. The entire show was set up as a fans’ fantasy set list. “I Get Around,” “California Girls,” “Caroline No,” “All Summer Long,” “God Only Knows,” “In My Room,” and the other 24-or-so chestnuts were precision-like replications of the original recordings, obviously lovingly assimilated by the orchestra and choir. Even the two instrumentals on Pet Sounds were trotted out successfully.

Not only did this evening not suck, but it was actually a watershed moment in time that I shall never forget.

In the appropriately selected Symphony Hall, I sat with tears in my eyes and triumph in my heart. It seemed, by the response after each song, that each and every audience member in the sold-out concert hall shared the same feelings, adoration, and respect, and that we were all in the same secret handshake Brian Wilson Society. At $65 a ticket, we got more than our money’s worth. In our senior years, we will surely take our great-grandchildren on our laps and tell them how we saw the great composer Brian Wilson perform all his masterpieces for the first time under his own name.

That is, unless Brian literally outlives us all the way he’s survived his entire nuclear (mother, father, and both his siblings) family. And I’m certainly not betting against that eventuality…